I’m really good at staring out of the window. In fact, if there was a degree in it, I’d be teaching it. It would be my Mastermind specialist subject. I can even stare out of the window when there’s no window to stare out of. The best windows are on trains. Especially backwards. Then you can see where you’ve been. And reflect on it…

Anyway this year, I moved my desk from under a rooflight (top quality sky staring and excellent snowflake examination) to a window that overlooks a field, some trees, a road, and a racehorse training track. It also has a lamppost, a dead tree that the pigeons nest in and a bus stop.

I’ve stared at it a lot.

Partly because I’ve been writing a book that’s been the hardest to write, ever. Perhaps it was the pandemic – perhaps because those chats that would have happened in real life had to be Zoomed and I feel so uncomfortable on Zoom that I can’t concentrate on anything anyone says. And partly because it’s just an ambitious book to write. There have been quite a few drafts – so many I’ve given up naming them by anything but date. The most recent has winged it’s way to my very patient editor. But I’m hoping perhaps, now, that I’ve cracked it.

For anyone that read the Boy Who Flew – it’s kind of similar – in that it’s warped history. History that didn’t happen, that might have done.

I learned about that at a young age from my writing gods, Joan Aiken and Leon Garfield. Both of them wrote books that I hung on to, cherished, re-read, and both of them used history to tell stories for children of now. If you’ve never read Leon Garfield – his writing is dark, magical, visceral, funny, and full of blood and love. His links to historical events are vague, his characters are on the edge of society, forgotten, able to witness things that others might overlook – and sometimes, they’re dead.

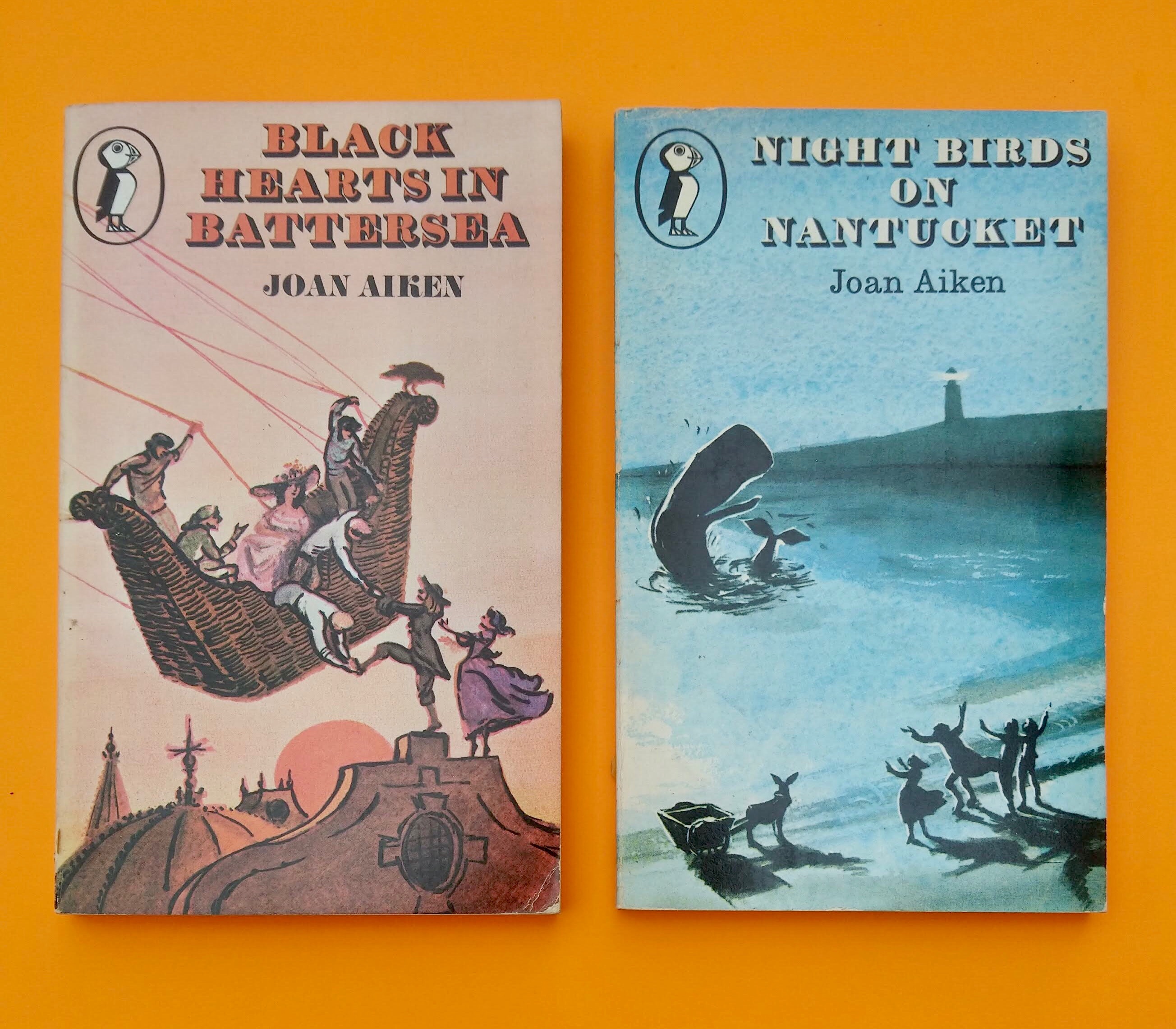

Aiken’s historical books are more loosely related to history – so loosely related, that she invents imaginary kings, and imaginary times. As a child I thought it was real history, it was only when I read Black Hearts in Battersea to my children that I realised it was like a tuck in time – history as it might have been – not as it was. She accompanies all this with extraordinary characters – I’ve talked at great length about this with Jake Hayes – and Dido Twite remains my very best ever children’s book character.

I have loved both their books for more than 50 years – and I still find new ones to read. But only recently have I realised how much they influence my work. Yes, I’ve read Dickens, and yes, there’s a bit of that in the Boy Who Flew, but Garfield and Aiken were my filters on the past. Not least because they wrote about the 18th Century not the 19th. Less of that Victorian orphan/governess/poorhouse/factory thing, and more of the dark/lawless/pre-industrial/grubby countryside thing. Think Henry Esmond and the History of Tom Jones, rather than Little Dorrit. It attracts me as a reader, and as a writer.

So the painful long manuscript that’s heading through the airwaves to my long suffering editor, is also set in an imaginary reign. Where the Boy Who Flew was set in an fictitious time somewhere towards the end of the 1770s – Mouse Heart is set in an imaginary 1710s and has an actual imaginary Queen. Queen Anne II – who never existed. But would have been excellent if she had. (Writing an imaginary queen is the best fun – no-one can tell me that she wasn’t like that – because of course she wasn’t.)

This must have been what Joan Aiken thought when she swapped the world around to give us the rambunctious characters that people Black Hearts in Battersea – where elderly Scottish kings stay in mansions alongside the Thames. It freed her from the tyrannies of “real history” and allowed her to play with the habits, language, limitations of the time, without worrying too much about the real politics.

Or perhaps she just knew that children would love the characters and wouldn’t mind a bit when or where it was set.

Either way. She gave me an excuse to invent my own queens, repurpose an actual city (Bristol), bring theatres that would have collapsed years earlier back to life, mangle Shakespeare, and hopefully entertain children, all at the same time.

You can be the judges.

Mouse Heart will be published by Nosy Crow in August next year.

I’ve not read either of those authors, so will be happy to add them to my stack. I do enjoy creating my own world for my characters. When they move into real time and space I like the research to make sure they touch the right places, and use the right tools for the period. I have to admit that there are folks that still criticise, and that is very disheartening, especially if they themselves are wrong.

On a nicer note, your new view sounds captivating. I’m guesing I’d get very little actual work done with that kind of prospect!

I look forward to Mouse Heart. Will there be pre-orders soon?

E

It’s a minefield. I remember my father endlessly noticing anomalies in second world war films – and there are plenty of people who love to find holes, so I find drifting away from the exact truth a great relief! My new view is indeed a joy. Compared to a wall it’s fabulous!!!

And yes, thank you, I think you can pre-order already. Nosy Crow has a link to the usual suspects… https://nosycrow.com/product/mouse-heart/

I absolutely loved The Boy Who Flew, as someone with very fond memories of Bath from student days back in the 80s I loved your portrayal of the dark, historical setting. I’m really looking forward to reading Mouse Heart, adding to my shopping diary for next year & will keep a lookout on NetGalley in case I can review an early proof 😊

Oh wow! Thank you!! I have no idea about things like Netgalley – but it might appear there.

Fortuitously I ‘m just writing an introduction to a new edition of Wolves, and Joan Aiken’s original inspiration about taking history and re-shaping it.

In her own words:

“Best of all, it occurred to me that the story should be laid, not in the reign of Queen Victoria, but under a different line of kings – supposing Bonnie Prince Charlie had become King of England and his descendants had kept the throne, then all the Georges, who should have come next would be lurking over in Hanover, plotting to dislodge them. This would leave me free to invent whatever I liked in my own bit of history.”

I like the Romans building their city of Bath in South America,, and that really dreadful Queen Ginevra, who mysteriously looks a bit like Queen Victoria…who we haven’t had yet! The dangers of free invention…

By the way the piece you link to is not in fact by me, but I liked it very much and she gave me permission to use it.

Thank you Lizza. That’s really good to know.